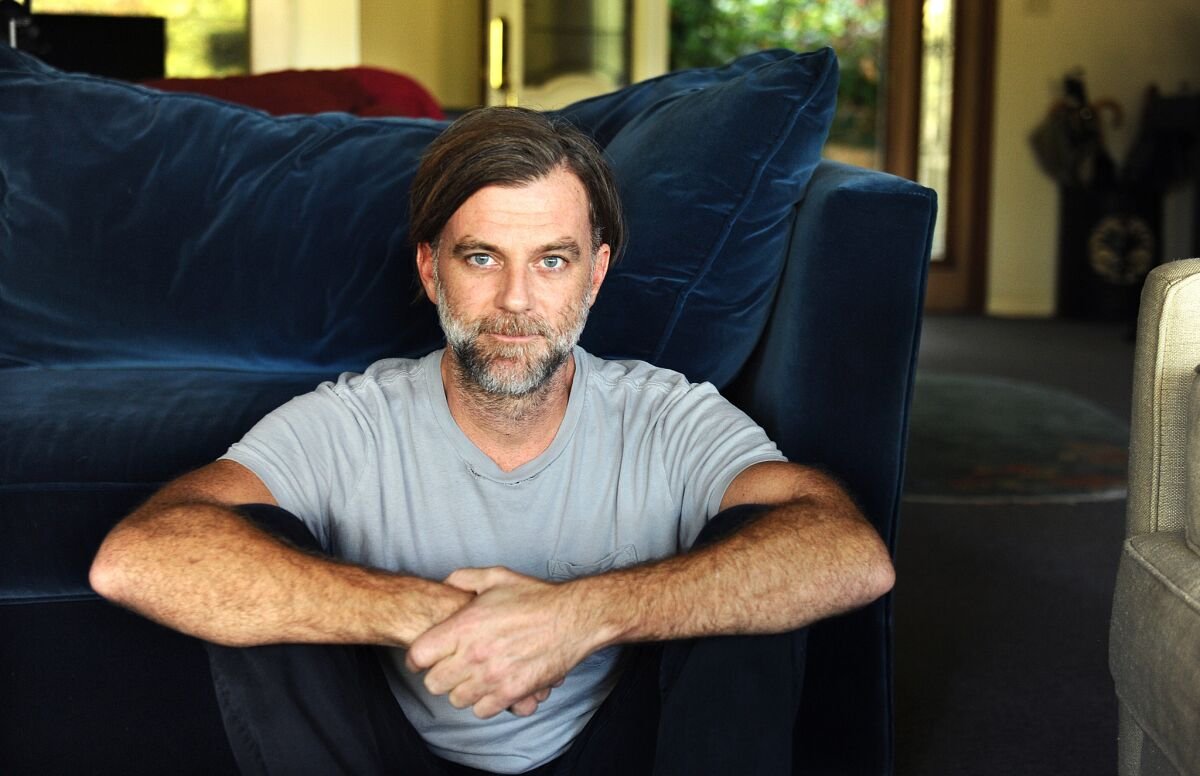

How Paul Thomas Anderson Became PTA in 10 Years

It’s the 1998 Academy Awards, and the award for Best Original Screenplay is up next. Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau read out the nominees, Woody Allen for “Deconstructing Harry,” James L. Brooks and Mark Andrus for “As Good As It Gets,” Matt Damon and Ben Affleck for “Good Will Hunting,” Paul Thomas Anderson for “Boogie Nights,” and Simon Beaufoy for “The Full Monty.” As Lemmon opens the crisp white envelope and reads excitedly that Affleck and Damon have won their first Academy Award, Anderson (another first-time nominee) screams internally and probably externally when he returns home from the ceremony. As his then-girlfriend at the time, singer-songwriter Fiona Apple, recounts, when he got home from the ceremony, he threw a chair across the room in a fit of rage. In the first ten years of Anderson’s working career, he turned some of that anger into art. He went from Paul, a kid from California who loved cinema, to the iconic PTA.

Paul Thomas Anderson was born in Studio City, California, on June 26, 1970. His father, Ernie Anderson, was a television personality and voice actor; his mother, Edwina, was a stay-at-home mom. His parents divorced when he was eight, and his mother chiefly raised him. His older siblings always overshadowed him; growing up, he glorified his father and continuously tried to find a path into his inner circle of Hollywood executives and fellow television personalities. Anderson became interested in filmmaking at a young age and started making little movies with his father's 8mm Betamax camera. He used to film his dad’s conversations with his friends, and once he captured a time when his dog swallowed and then passed an entire orange. Anderson is part of the “video store” era of filmmakers, the first generation with older films at their disposal thanks to video rentals and archive footage. He spent his teenage years developing his taste at the video store on Vineland and Ventura and through watching movies at the Cineplex Odeon. Anderson is a proud Southern California native, another factor of his identity that shapes his films.

He attended multiple schools growing up, including the Buckley School in Sherman Oaks, Campbell Hall School in Studio City, and Cushing Academy, an elite boarding school in Boston. He hated boarding school and convinced his family to let him move back to California. As an adolescent, he used to hang out with a group of kids of Los Angeles elites, who used to comment on Anderson’s restless edge and twang of anger. His teachers and friends expressed he was a “trash-talker.” His friends recall that one day at a casual game of tennis, Paul freaked out and threw his racket at a friend. After finishing high school, Anderson went to Emerson College for two semesters before transferring to New York University's Tisch School of the Arts to study film. His first NYU professor declared with utter seriousness that if anyone is to write a movie like “Terminator 2,” they should “get out” of the class because NYU is for real writers. Paul grew up loving “Terminator 2,” which was his first point of friction with the University. In another class, he turned in Pulitzer Prize winner David Mamet’s screenplay for an assignment as his own work, and the professor gave him a C; Anderson immediately knew that film school would only hold him back. After only two days, he dropped out of NYU to focus on making films. He said, “Film school is a complete con.” He began living off of the money that NYU repaid him, and he quickly got started on a short film. In an interview with the LA Times, Anderson explained that his “filmmaking education consisted of finding out what filmmakers I liked were watching, then seeing those films.”

Anderson’s first feature-length film, “Hard Eight,” was released in 1996. The making of this film began when Anderson, who was still a student, wrote a script titled "Cigarettes and Coffee," which was made into a short film in 1993 starring Philip Baker Hall. He sent the script for “Cigarettes and Coffee” to Hall, who Anderson loved in Robert Altman's 1984 film "Secret Honor," where he played President Richard Nixon. The two met on the set of a film Hall was starring in and Anderson was PA for; they used to chat over the coffees Anderson brought him. The two became friendly, and Hall asked Anderson what he wanted to do with his life. He said, “Write movies,” then pitched a 28-minute film with a leading part for Hall. Hall was fascinated by the 23-year-old’s script and allured by his passion and confidence, and he decided to accept the role. Anderson came into his own in the 1990s, with other filmmakers who also came up during the indie boom that was a backlash and reaction to the overly corporate 80s movies that overtook box offices in the decade past. One of the reasons that Anderson is as revered as he is today is that he never went out of fashion, and he kept evolving as an artist, and Hall tapped into that. Anderson is not somebody who will be flamed out; he will not be a relic of the 90s. The film premiered at the 1993 Sundance Film Festival, and after the short, the Sundance Institute invited him back to create a feature-length version of the film. Anderson titled it “Sydney.”

In the early days of pre-production, Anderson had some problems securing funds for the film, but he was able to confirm financing from Rysher Entertainment. He cast the rest of the roles, including John C. Reilly, Gwyneth Paltrow, and Samuel L. Jackson. Filming took place over a quick 28 days in Reno, Nevada. Anderson chose Reno as the background because he sought to seize the worn-down, rundown feel of a city that has never been great. The crew met considerable shooting problems, including harsh weather circumstances, financial limitations, and studio troubles. Anderson has voiced how influenced he is by the editing style of Robert Altman and Martin Scorsese, which, unfortunately for this film, wasn’t seen at large. But this wouldn’t stop Anderson. Even though he spent months editing the film after production wrapped, he lost the film’s final cut, which was re-edited and retitled “Hard Eight.” It appears certain that the people who funded the film barred him from the editing room to make it short and more commercially acceptable, and this was incredibly painful for Anderson’s self-esteem. Actors Reilly and Hall were on Anderson’s side, and they said they had sore throats to avoid dubbing that film cut. "Hard Eight" premiered at the 1996 Cannes Film Festival and received a complementary distinction. It was then released in cinemas all over the United States, where it acquired mixed reviews and, unfortunately, didn’t do well at the box office. Regardless, it has since earned a cult followership and is nowadays considered a critical success and quite impressive as a first feature-length film. His skill for crafting compelling and nuanced characters, creating a distinctive visual style, and eliciting powerful performances from his actors while using inventive camera angles and lighting make this film special. Paul was only 26 when “Hard Eight” was released.

Anderson’s second feature, the 1997 film Boogie Nights, is the film that truly put him on the map as an artistic force to be reckoned with. He began working on it when production wrapped for “Hard Eight.” As stated previously, Anderson is a “Valley born and raised,” and the San Fernando Valley was home to the American porn industry in the 70s and 80s. Growing up, Anderson could tell the difference when the film sets near his home were for Hollywood movies and dirty movies. He was intrigued by porn filmmaking’s seductive charisma, relaxed culture, and intent of creating a family on set. In 1988, when Anderson was still in high school, he shot a mockumentary film titled “The Dirk Diggler Story,” about the rise and fall of a fictitious porn superstar. Anderson cast Micheal Stein as his lead because he was a “freak.” In this short film, you first ingest Ernie Anderson's overripe announcer's voice over a dark screen, poking fun at Dirk Diggler: “He was born Steven Samuel Adams on April 15, 1961. His father was a construction worker; his mother owned a popular boutique shop.” The short film was only 32 minutes long and carried primary inspiration from Rob Reiner’s 1984 mockumentary, “This is Spinal Tap.” He shot most of it in a shoddy hotel next to Universal Studios, only using a video and steady camera that his father donated to the project. Anderson’s main note to the actors on set was that he expected this film to be taken seriously because the characters took their professions seriously. Even in its graininess and off-frame rate, you can feel that Anderson is an actor’s director. He sees the potential in those that the rest of the industry does not; he can tap into that rage and aggression he feels within himself and transform it on screen.

In 1996, Anderson worried about working with studios for the feature-length film (now titled “Boogie Nights”) because of what happened with “Hard Eight.” But Micheal DeLuca, a producer at New Line Cinema, was ready to take on his project because he wholly believed in Anderson’s artistic vision. As casting began, many actors were regarded for the now-iconic leading part of Eddie Adams, better known as Dirk Diggler. Leonardo DiCaprio, Joaquin Phoenix, Christian Bale, and Ethan Hawke were considered. Anderson knew this role needed to be filled by a superstar, as one of Dirk’s best lines is: “I am a star. I'm a star. I’m a star. I’m a star. I am a big, bright, shining star.” Anderson’s first choice was DiCaprio, but DiCaprio wasn’t sold. He dropped out to star in “Titanic” (1997) and advised past co-star Mark Wahlberg for the part. Wahlberg was slightly uneasy about playing a porn star but accepted because he loved the story, and Anderson loved his authentic, egotistical, and heartbreaking portrayal of Dirk.

On paper, the most impressive person to sign on to the project was Burt Reynolds, who was set to portray the critical supporting part of a pornographer and surrogate daddy, Jack Horner. Yet, despite this role gaining him an Oscar nomination for the best-supporting actor, Reynolds didn’t like the script or the director. The two used to fight on set, and Anderson used these authentic confrontations to inspire one of the best scenes in the film, when Dirk, high out of his mind, picks a fight with Jack right before he needs to film a scene. What makes “Boogie Nights” so different from other films featuring the porn industry is that it’s not a sexy movie, and one could argue that it’s not even a movie about porn; it’s about family. Anderson uses his own family experiences in the film, notably his history with his mother, in a scene with Dirk and his mom right before Dirk runs to Jack Horner’s porn house. The scene is hilarious and absolutely heartbreaking; Dirk cries and screams to “not be mean to me” as snot drips into his mouth while his disapproving Mom rips down his posters. “Boogie Nights,” at its core, is about ambition, desire, addiction, the commodification of sex and human relationships, and the ability to heal.

After the immense success of his last film, New Line Cinema decided to let Anderson have total control over his next film. Anderson knew this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and would run with it. “Magnolia” was released in 1999, and to say it’s a different beast is an understatement. PTA’s over three-hour ensemble piece about lost souls in Los Angeles is one of his most intellectually ambitious films. During the long editing period of “Boogie Nights,” Anderson was already writing down ideas for his next project. Anderson seems to constantly need to be stimulated and enthralled in his work, which can manifest in his obscure characters wanting to be seen and heard in his narratives. Part of “Magnolia’s” magic is that every unique character has the same goal: to be listened to and loved. Anderson was given the final cut on “Magnolia;” this movie would be executed exactly as he pleased. He knew the film’s title before he even had a screenplay. He originally intended for this film to be intimate with a short 30-day shoot, but ideas kept flowering and blossoming like the title as he kept writing. Heavily inspired by Robert Altman’s 1993 film, “Short Cuts,” he envisioned new settings, actors, and small details to create one epic, Californian story. “Magnolia” is quite iconoclastic; its screenplay employs various literary techniques to develop a sense of unity and cohesion between the different chronologies. For example, several characters share similar experiences or themes, such as fatherhood, betrayal, or regret. The film also uses recurring motifs and symbols, such as the color blue, the number 8, and the song "Wise Up," to create a sense of interconnectedness and foreshadowing. He utilized many of the same ensemble cast members of “Boogie Nights” in “Magnolia,” as well as other Hollywood stars, notably Tom Cruise, who plays Frank TJ Mackey, a men’s rights motivational speaker. This film didn’t come from the pure abyss of PTA’s imagination; before he was a filmmaker, he worked as an assistant on a game show for kids, a critical location for “Magnolia.” “Magnolia” also deals with death and the process of dying, which Anderson was able to draw from his own experience of watching his father die of cancer. While Anderson was pleased with his deal from New Line Cinema, he strongly opposed the film’s marketing and insisted on control of that side of post-production. He hated the “Boogie Nights” trailer and poster, and for “Magnolia,” Anderson ended up cutting the trailer himself and conceiving the poster. While his third film was messier, more ambitious, and perhaps overly philosophical, “Magnolia” has a soulful, contemplative melancholy that feels like taking a giant exhale.

As Anderson waited for the release of Magnolia, he wrote the screenplay for his next film, “Punch Drunk Love,” in two weeks. He was set on casting Adam Sandler as his lead as he grew up loving Sandler’s movies as a child. He claimed that Sandler “gets me.” As he established his technique and personal style with his earlier flicks, he wanted to challenge himself with a ninety-minute-long romantic comedy, significantly dissimilar to the dramas he made in the past. Anderson cast Sandler in the lead role of Barry Egan, a lonely, socially awkward man who falls in love with Emily Watson's character, Lena. Anderson had been a fan of Sandler's comedic work but wanted to see him in a dramatic role. Emily Watson was cast after Anderson saw her in the film “Angela's Ashes.” Anderson got the inspiration for this film from both being a devotee of Sandler’s comedic style and after hearing the true account of David Phillips, a man who earned millions of frequent flyer miles by buying enormous quantities of dessert pudding cups. Anderson included this into the film’s narrative, with his main character Barry Egan amassing a gross amount of pudding for frequent flyer miles. While Anderson set out to make a more conventional movie, perhaps more digestible to the typical American movie-going audience, he used several experimental techniques in filming, such as handheld cameras and unconventional lighting, to elevate his version of a romantic comedy. The editing process for "Punch-Drunk Love" took several months, as Anderson and his team experimented with different cuts and pacing. The film's score, composed by Jon Brion, was also an integral part of editing. Brion's score features a lot of percussive instruments, including xylophones and marimbas, which give the piece a playful and whimsical tone and mimic the protagonist’s unstable and shifting moods. Though this is a romantic comedy, this is PTA. The film explores the concept of capitalism and consumerism, with Barry's job as a salesman and his obsession with collecting frequent flyer miles representing the emptiness and superficiality of modern society. However, the film ultimately suggests that even in a world dominated by materialism and superficiality, there is still the potential for genuine connection and love.

And this is just the first ten years of his working career. At this point, he hasn’t gone on to adapt Upton Sinclair’s novel, “Oil,” into “There Will Be Blood,” a film widely considered one of the best of the century, nor has he written “Licorice Pizza,” his unmistakable love letter to the San Fernando Valley in the 70s. As he ages, his directing style has become less kinetic and frantic and more introspective and philosophical. Yet, in all of Anderson's movies, his characters try to reinvent themselves with new identities and personalities as they discover what makes them happy to be alive. Many events in his childhood became the cinematic motifs that would materialize in his forthcoming films, proof of his unique ability to convert the details of his life into a creative entirety. The most unifying component is perhaps his uncommon but special capability of capturing aggression, whether physical or psychological, which shifted his camera into a weapon. While his films feel comical at times, there is a dark edge that explores the shaded side of masculinity, loneliness, and searches for self, all of which come from his own struggles as he grew into himself. In these first ten years of work, he focused his creativity on a character who looks up to and finds a father figure in a gambler, another who becomes a porn star after fleeing a toxic home environment, and another who comes up with a peculiar scheme to escape his suffocating life and struggles with depression through bulk purchases of grocery store pudding cups. These characters feel like outsiders and repeatedly find themself in unusual workarounds when the dominant, bourgeois social norms aren’t serving them, and their creator is even more so.