Norman Fucking Rockwell!: Hollywood is a Hoax and America is Dying

“Ugh, fuck! I miss 2019 so much.”

“Bitch, me too! Like, TikTok was actually funny, Igor was poppin’ off, and Toy Story 4 just came out.”

I so badly wanted to chime in and say, “So did Once Upon a Time in Hollywood!” God, I love that movie. I could literally talk about it for hours, and I have before, but I don’t think those girls ahead of me at Starbucks would have liked that. I’ve been trying out this new thing called “don’t talk people’s ears off about movies you like.” It’s mostly a rule I have for house parties.

Because my AirPods died quickly during my wait in the seemingly endless line, I chose to eavesdrop on their entire conversation. They were close enough that I could smell their caramel perfumes.

It felt weird to hear two girls in my generation express so clearly their adamant nostalgia for a time that was only five years ago. Aren’t we a little young to be nostalgic? Those feelings should start later, right? They spit out a couple more niche pop culture references before they had an exchange that made my heart sink a little. Maybe I’m older than I thought.

“I know, I just said I miss a fuckin’ metal water bottle, but do you know what I mean when I say that something in the air was just different back then? Like even water bottles aren’t the same now. Can’t describe it. Life was, like, good. And then it got really bad.”

“Yeah, like we didn’t know what was about to hit us.”

For a couple of minutes, I found it really cool that I knew the Tyler The Creator songs they mentioned and that in my bag, I had a Hydroflask, one of those “fuckin’ metal water bottles” they discussed. My ex-best friend from high school gifted it to me for Christmas in sophomore year six years ago. Had it really been that long? I wondered if she would be mad that I dented the water bottle so badly that the paint chipped. Probably not madder than when her ex became my boyfriend, who then also became my ex.

I was forced to stop thinking about my messy high school drama and how I would always be subtly connected to my ex-best friend when it was my turn to order. I felt a wave of decision fatigue, and I copied the drinks those girls got: a vanilla almond milk latte. I never get those. I would probably get it again.

I tend to make things deeper than they are, but their conversation felt deep and real to me. In between the hyper-consumerist nods and dated digital catchphrases, they verbally captured the experience of disillusionment within a culture on the verge of collapse that Lana Del Rey did in her 2019 album, “Norman Fucking Rockwell!” It was just communicated in a different way.

“The culture is lit, and if this is it, I had a ball.” (“The greatest”)

Like I already said, I make things deeper than they are. And Lana Del Rey is my favorite; when she sings, I feel like I can see the lyrics come to life in my head, playing like a movie no one else can see. Her songs have instrumentals that feel like they belong in an end-credits sequence of a melancholy, sun-soaked drama set in Los Angeles, California. The guitar chords and hazy production echo a Tarantino film’s atmospheric, reflective soundtracks, where nostalgia meets an aching awareness of the present's imperfections. In Norman Fucking Rockwell!, Del Rey crafts a world steeped in apocalyptic nostalgia, using vintage Hollywood aesthetics and wistful Americana in the cover art and music videos to comment on America’s cultural stagnation. The album’s lush sound editing and throwback motifs feel like a love letter to and an elegy for a legendary American history—a golden age that never truly existed. But almost did. And maybe still could.

“The California sun and the movie stars, I watched the skies getting light as I write, as I think about those years.” (“How to disappear”)

Its release in 2019 feels important to say again. Norman Fucking Rockwell! landed on the American cultural landscape like a prophecy, its themes of decay, disillusionment, and longing eerily prescient in light of what was to come. Just months before the world was thrown into unprecedented disarray due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Del Rey seemed to channel a sense of impending doom intuitively, her lyrics hinting at the fragility of the cultural systems we’ve taken for granted.

Hollywood, a star muse for Del Rey, looms large on the album as a symbol of enduring mythos and an industry teetering on the edge of decline. In her other albums, her portrayal of Hollywood is soaked and sparkles in timeless glamour, yet there’s an undercurrent of melancholy in NFR—a knowing divulgence that icons always fade.

The 2020 pandemic pierced the entertainment industry hard, especially cinema–my favorite thing after Lana Del Rey music. It shut down movie theaters, halted production, and brought box office numbers to unprecedented lows. Streaming services full of mediocre, half-baked content surged, and the traditional Hollywood model, built on the collective experience of a love of the cinematic and the grandeur of the silver screen, met an existential crisis. I don’t want to sound like a snob because I know that movie theaters are back now, and “real” movies are being made and released. But it still seems like most people would rather watch the new Netflix or Hulu Original series at home than watch a film in a theater–the way the art was intended to be viewed.

"Whatever’s on tonight, I just wanna party with you." (“The Next Best American Record”)

Yet, as Del Rey seemed to anticipate, Hollywood’s mythology confirms resilience uncannily. Like the Golden Age imagery she conjures in her songs, the concept of Hollywood lives on–even in times of decline and hardship–as a shared cultural touchstone. The kinds of movies being made are different, too. I know it might sound obvious—and lame because I feel a weird longing for a time I didn’t live through (I guess I am old enough to feel nostalgic)—but the themes explored in cinema and the overall quality of filmmaking have shifted dramatically from when going to the movies felt special to the post-2019 era where nothing feels sacred anymore. NFR captures this tension perfectly: it’s both a requiem for a bygone era and a meditation on the cyclical nature of cultural reinvention.

It makes me feel genuinely sad that cinema (but honestly art as a whole), was once a refuge of profound human connection, but now often feels as disjointed and disillusioned as the society it reflects. I felt it in my soul when Lana sang both “as summer fades away, nothing gold can stay” and “fresh out of fucks forever” in the 9-minute track “Venice Bitch”. Because while I do feel sad about the intersection of American societal trends and artistic production, what the fuck am I going to do about it? I sound lazy and passive, but really, tell me. Having a sort of compassion fatigue for an industry that used to be something greater feels wrong. And it’s fatiguing.

“Your poetry’s bad, and you blame the news, but I can’t change that, and I can’t change your mood.” (“Norman Fucking Rockwell”)

But why must there be a movie about everything and everyone now? I’m so sick of the corny biopics about bands/musicians and zombie apocalypse movies that are metaphors for COVID-19. Oscar Wilde once said that “life imitates art far more than art imitates life.” I want to believe him.

Del Rey suggests that while the systems we rely on may erode, their stories will endure, and they will mirror our collective nostalgia and our simultaneous fear of moving forward. In “hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have,” she refers to herself as a “24/7 Slyvia Plath”, identifying with the burden of being an artist in an industry that demands constant availability and commodifies vulnerability.

“I’ve been tearing around in my fucking nightgown, 24/7 Slyvia Plath, writing in blood on the walls ‘cause the ink in my pen don’t work in my notepad, don’t ask if I’m happy, you know that I’m not.” (“hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have-but i have it”)

To the average Lana fan, like myself, it’s common knowledge that she’s known for referencing celebrities in her lyrics and music videos–more often than not, Old Hollywood stars. Del Rey’s music has always felt like it mourns a world that feels like it’s slipping away, and Old Hollywood represents a "golden age" to romanticize. Her references in albums before NFR read as a longing for a time when fame, art, and beauty were seen as more romantic and less diluted by today’s hyper-commercialization.

The first Lana song I ever heard was Blue Jeans in 2012. I loved it when she sang, “It was like, James Dean, for sure, You're so fresh to death and sick as c-cancer.” Even though at 9 years old, I had no idea what that meant or who James Dean was. I just knew it was cool.

“I miss the bar where The Beach Boys would go, Dennis’s last stop before Kokomo.” (“The greatest”)

The references in NFR feel so different. They are colder, darker, and more subtle. Which makes them even cooler. This album is undeniably centered on Hollywood and Los Angeles, and Del Rey heavily explores her perspective on their empty promises and warns that the illusion of the “American Dream” will only deteriorate more. The Hollywood machine is different from when the products it spit out were James Dean, Billie Holiday, and Lou Reed, all of who are referenced in Lana’s songs of prior records.

That girl in Starbucks was right; the world does feel different. Jake Paul just beat up Mike Tyson on Netflix’s first live-streamed event, and a former reality television star is about to be the President again.

“Kanye West is blonde and gone, Life on Mars ain’t just a song.” (“The greatest”)

You can’t truly discuss the album without discussing the title, named after American painter and illustrator Norman Rockwell. This title and album mock the modern idea as a Rockwell painting. His paintings all depict a particular flavor of the American dream and sometimes have a political taste to them as well. He was a prolific artist with over 4,000 pieces, ranging from portraits of Ruby Bridges being escorted to school by U.S. Marshals in “The Problem We All Live With” to a family eating Thanksgiving dinner in “Freedom From Want.” I feel weird when I look at them for too long.

I believe the essence of Lana’s album lies in recognizing that we’re living through a deep and turbulent chapter in American history, which commands artistic reflection, but what we have to show for this demand is disappointing. As an avid cinephile, this is where I see it the most clearly. This era is far darker and more disheveled than anything ever depicted in a Rockwell painting. That’s why the addition of “Fucking” in the title is so conscious;it’s a sarcastic exposure of the disparity. It’s as if to say, “Norman Fucking Rockwell, indeed.” Because Rockwell’s work romanticized the American Dream, the current reality—under a leader who insists that the dream is universal—just feels like a pervasive circus.

The music videos accompanying the album feel like mini vintage films, each imbued with a distinctly cinematic quality and with a sick title card (title card fonts are one of my favorite parts of movies). Del Rey has long been celebrated for her visual storytelling through both her lyrics and videos, which draw deeply from Hollywood nostalgia and Americana. In “Doin' Time”, a towering Lana roams the streets of Los Angeles, paying homage to the iconic Attack of the 50-Foot Woman (1958) and the campy charm of Hollywood’s B-movie era. The whimsy of the video is cleverly juxtaposed with the song’s underlying melancholy about frustration, betrayal, and vigorous confinement within a relationship. The song’s title is a metaphor for feeling trapped, and 50-foot Lana stepping out of the silver screen into the real world where people are watching her in a 50s-style drive-through movie theater is meta in the coolest way.

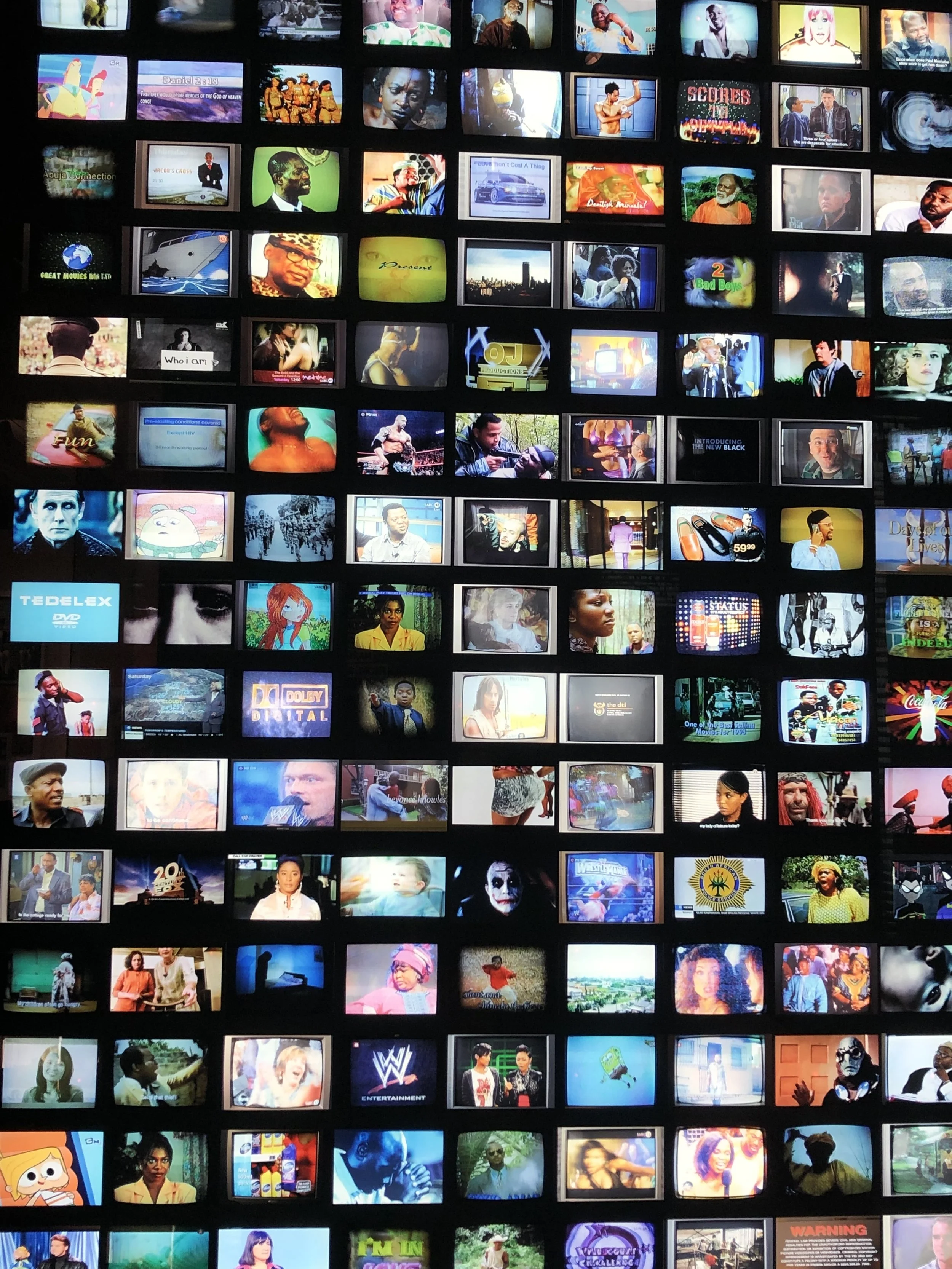

The title track’s music video, Norman Fucking Rockwell, is packed with dreamy sequences of yachts and sunsets, visually recalling the languid, coastal glamour of 1970s films like The Long Goodbye. There is a sunlit elegance tinged with a subtle lethargy and emotional exhaustion as Lana lazes by the pool in sunglasses with lenses like circular mini-movie screens. Similarly, the video for “The Greatest” uses retro VHS filters to capture a sense of faded Hollywood grandeur, juxtaposing idyllic, almost fantastical pictorial elements with existential overtones.

If this album were a film, it would undoubtedly be set against the evocative backdrop of Los Angeles, California. The Golden State is both muse and metaphor—a cinematic tableau where aspiration and decay intertwine, like the sprawling suburbs of LA, interconnected by vast highways that seem like they could stretch on forever.

When I have my moments of wanting to be melancholy and reflective (which feels like it’s more now than it used to be), Norman Fucking Rockwell! is immediately where I escape to. It's as though she captures the unspoken emotions I've always carried but could never articulate myself. I guess this is what it feels like to live through an era on the brink. I’m hoping that’s not true.