Blaise Pascal and Bojack Horseman: Exploring Existence through Philosophy and Postmodernism

My whole life, I have spent much of my free time thinking about the purpose of my life. I go to school, hang out with friends, go to the occasional party, go to the gym, and eat relatively healthy, but why? I don’t have to do those things; society has just conditioned me into believing that these are the things I’m supposed to do to be a good person. But why does being a good person even matter? Since I was a young child, I always thought about questions that no one could answer for me, like, “what happens when we die?” or “what is my purpose?” These may sound like broad and mildly depressing questions to ponder, and honestly, they are. The more I think about it, the more uncomfortable and upset I get. No one knows the answers, and if they say they do, that’s just their personal beliefs. As I have gotten older, I have become comfortable with the fact that life’s purpose and our existence is an unknown entity. No one can answer those burning questions about our existence. I have learned to be okay with just how outlandish being a human can be. I account for much of this stoicism from the Netflix original series, Bojack Horseman, and 17th-century philosopher Blaise Pascal’s Pensees.

Pensees was written as a defense of Christianity, but Pascal died before the book could be fully edited and published. Thus, the Pensees exist as a series of fragments. Pascal was ascetic and takes extreme positions on the subjects he writes about. This postmodern adult animated show condenses all my questions about existence into the main characters because of how it uses the ideas of Pascal to propel the narrative forward. By using Pascal’s ideas from hundreds of years ago, the show claims that humans have been pondering these questions of existentialism, purpose, and perception for centuries; it just takes on new forms as society evolves.

Bojack Horseman is six seasons long and takes place in a universe where humans and anthropomorphic animals live side by side, mainly in Hollywoo, California (the name is changed after the D from the sign is stolen). The show centers around a humanoid horse Bojack Horseman (Will Arnett), struggling deeply with substance abuse, self-loathing, and mental illness, who wants to make a comeback in the entertainment industry. He was once the star of a popular 90s sitcom titled, Horsin’ Around, and as he works on his commercial redemption, he realizes how much the industry has changed and his faults as a horse. The show’s light and bright veneer juxtaposes and hides the dark and depressing themes. The show’s main characters move through the dazzling facade of Hollywoo only to discover how ugly and selfish it is; Hollywood is revealed as a metaphor for existence in general; it means nothing. The five main characters all face different internal and external obstacles, but all confront the main question that the show poses: if life is truly meaningless, how are we supposed to deal with it?

I always thought that show was a great way of exploring the bleak fate of humanity, even though half the characters are not human, and all the characters are animated, but I couldn’t pinpoint why. Upon finishing the series, I researched the questions and ideas that the main characters ask each other and themselves to further my understanding of the meaning of this television show. This brought me to the learning the concepts of Blaise Pascal, and how/why the show’s artistic choice to be animated is a postmodernist way to represent nihilism and absurdity. Before understanding how the actual visuals of the show are essential to the narrative and themes, the show’s major success at tackling existentialism and existence is rooted in its inspiration from Blaise Pascal, who found people’s disinterest in their existential dilemma fascinating. These are precisely the themes that Bojack Horseman covers through its six seasons.

“As I know not whence I come, so I know not whether I go. I know only that, in leaving this world, I fall for ever either into annihilation or into the hands of an angry God, without knowing to which of these two states I shall be for ever assigned. Such is my state, full of weakness and uncertainty. And from all this I conclude that I ought to spend all the days of my life without caring to inquire into what must happen to me”(Pascal 194).

Throughout the show, the main characters ask many of the same questions that I do. Who are we? Do we matter? Does anything we do matter? If it doesn’t, why should we do anything? Bojack Horseman successfully portrays an array of disorders that come from existential crises but does so in a way that does not offer the audience any tangible solutions to these problems. The show does not blame one event that triggers mental illness or substance abuse. It depicts through the six seasons how many events and series of decisions can compel one into feelings of distress, inadequacy, and corruption.

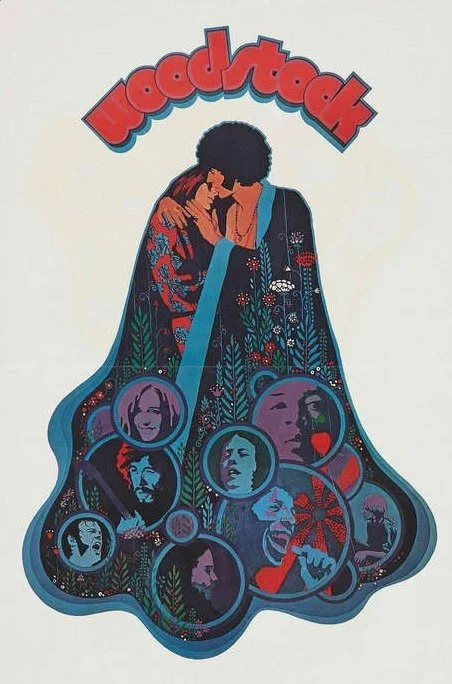

When I first started watching this show, I assumed that this was a light-hearted, adult animated comedy. I have always loved other animated shows aimed at adults like The Simpsons and South Park, and I thought that Bojack Horseman would be similar just from looking at the poster. What sets this show apart from other adult animated comedies is that this is a post-modernist show, meaning that it serves as a bridge between philosophy and art, the art, in this case, being cartoons. In Megan Kirkwood’s article published on Medium, The Postmodernism (and Nihilism) of BoJack Horseman, she explains that

“Modernism valued realism and naturalism, rationalism, objectivity, reason, personal experience, individualism, liberal capitalism, business, and technical fields. Contrast this to the premodern period which valued obedience, religion, classicism, and the inherent sinfulness of man, and we see a move towards more modern notions of personal autonomy and societal development. However, the postmodernist disagrees with both the pre-modernists and modernists. Postmodernism rejects ideas of realism and objectivity, and values anti-realism, social subjectivism, anti-truth, egalitarianism, socialism, and the humanities. Postmodernism denies the existence of objective truth, that we can never know if there is or is not a “real” outside our human experience.”

By using cartoons to represent philosophical themes and the existential crises that the characters are going through, the audience can more clearly understand the post-modernist storytelling techniques that push the philosophical themes forward. These post-modernist storytelling techniques include narrative and non-narrative episodes and different animation styles to showcase characters’ messy mental states, which are opposite from a 90s-style sitcom that the show discusses, making the show complex, unpredictable, and highly self-aware.

The show displays many sides of how people deal with their existence through distinct character development and arcs, representations of mental illness, family dynamics, and healthy and unhealthy coping skills through a philosophical lens. Each main character of the show echoes the principles of Pascal, proving that when given too much time to think, humans will eventually contemplate their insignificance, which in turn creates the need for distractions like drugs, sex, and alcohol to fill the void that exists within us all. To quote Pascal,

“I have discovered that all the unhappiness of men arises from one single face: that they cannot stay quietly in their chamber. I have found that there is one very real reason, namely the natural poverty of our feeble and mortal condition, so miserable that nothing can comfort us when we think of it too closely”(139).

The characters struggle with self-perception and low self-esteem, and they are aware of it. The main characters constantly find completely different but temporary fulfillment when they have tasks and jobs that allow them to shut off the perpetual dread within, which echoes Pascal’s point that “Nature then provides passions and desires suitable to our actual condition. We are only troubled by the fears which we ourselves (not Nature) create, because they add, to the condition in which we find ourselves, the passions of the condition we have lost (33)”, meaning that the human brain is conditioned to make us uncomfortable as a means of protecting us from the potential danger of the unknown.

Bojack Horseman is the show’s half-human, half-horse main character. The show follows Bojack as he is past his prime. He is now a middle-aged, washed-up television star with depression, substance abuse problems, narcissism, and an avid self-loather. He is bitter and constantly annoyed by his surroundings, which leads him to live a life of distraction. He trivially spends his days partying, relaxing, and doing things that don’t benefit himself or others around him. Bojack is an extremely famous actor and deeply struggles with this. Bojack has access to his every material need and want, and when he is still unhappy, he struggles to understand why. In Pensees, Pascal writes about why kings are not destined to be happy even though they seem to have their every need covered, and in modern times we can replace the word king with celebrity. “Yet, when we imagine a king attended with every pleasure he can feel, if he be without diversion and be left to consider and reflect on what he is, this feeble happiness will not sustain him”(139). Bojack is aware that being a celebrity will not bring him happiness, but he doesn’t know what will. “I’m responsible for my own happiness? I can’t even be responsible for my own breakfast,” says Bojack in Season 1. Bojack’s interest in making a Hollywoo comeback goes hand in hand with Pascal’s theory on kings; he believes he will be happy once he makes a resurgence. For Pascal, humans have an easy defense mechanism against uncomfortable thoughts of life’s meaning; we are easily distracted. Bojack searching for a Hollywoo comeback is a distraction from solving the root of his problems.

As stated previously, Bojack’s life is a series of distractions, and substances are a major issue for him. Bojack came from a troubled, loveless childhood with alcoholic parents and spent his formative years looking up to Secretariat, a famous racehorse from the 1970s. Bojack constantly watched Secretariat on the television and could always turn to Secretariat when times were rough. Bojack achieves his dreams of making a Hollywoo comeback by securing the role of Secretariat in a movie in the finale of Season 1. Bojack sees Secretariat as a godly figure, but in the shadows, Secretariat was deeply corrupted by fame. Secretariat commits suicide after being banned from racing for illegal betting. Even though he achieved a major goal, Bojack’s problems don’t suddenly dissipate; he still struggles with drugs and alcohol and still doesn’t understand his life’s purpose, which sends him into a further spiral of turning to substances. Because of Bojack’s tendency to force distraction to avoid the reality of his bad choices, his worst fear is the idea of radical freedom, which comes from 20th-century philosopher Jean-Paul Satre. “That is what I mean when I say that man is condemned to be free. Condemned, because he did not create himself, yet is nevertheless at liberty and from the moment that he is thrown into this world he is responsible for everything he does.” Sartre believes that there is no fixed morality or human nature to determine human action. He believes that people have the absolute power to choose how they will act in any given situation and in their lives, which Bojack hates because he constantly makes the wrong choices. Bojack is self-aware enough to say in Season 3, “I stand by my critique of Sartre. His philosophical arguments helped many tyrannical regimes justify over-cruelty.” The ideas of Pascal don’t align with that of Satre; Pascal believes that humans should turn to God instead of distraction to save themselves, “It is unnatural blindness to live without seeking to know what we are; but it is dreadful blindness to live a bad life while believing in God”(399).

Because Bojack represents what happens when humans reject the ideas of Pascal and Sartre, in a mentally unwell state, he forces distraction upon someone he cares about, which is a decision he regrets and will eventually pay for the rest of the series. He reaches the critical point where diversion cannot sustain him; he pushes his poor mental state and substance problems onto others, notably his Horsin’ Around co-star, Sarah Lynn, a former child star who is now a pop star. In Season 3, he and Sarah Lynn go on a month-long bender, which results in Sarah Lynn dying of a drug overdose. In the show, we see that Bojack had the potential to save her life but selfishly didn’t, which is a decision he deals with for the rest of the show, further proving Pascal’s point that humans have trouble sitting alone with their thoughts, especially when they know they made the wrong decision. The show’s writing is cognizant; Bojack himself says, “Am I just doomed to the person that I am? I know that I can be selfish and narcissistic and self-destructive, but underneath all that, deep down, I’m a good person, and I need you to tell me that I’m good.”

The show addresses identity and personality issues, and Boajck’s name and appearance are other postmodern ways that the show spells out his simultaneously predictable and unpredictable personality. His last name, “Horseman,” gives him a pre-existing label and representation of what he is supposed to be, and his half-human, half-horse body shows his struggle with human nature and animal instinct. He often has the instinct to know the right thing to do, but his nature stops him; we see this clearly when he doesn’t save Sarah Lynn’s life. Bojack is aware of this internal battle, and it is the driving force behind his self-loathing; he knows the right things to do, and he doesn’t do it. Pascal writes about how the only cure to self-hatred is to do the opposite as he writes, “as we cannot love what is outside ourselves, we must love a being within us, who is not our self, and hold true of each and every man. Now only the Universal Being is of such kind. The Kingdom of God is Within us, is our self and yet not our self.”(327) None of the characters, but notably Bojack, give themselves grace that isn’t narcissistic and toxic, creating miserable characters with a plethora of mental problems.

Most of the show’s philosophy and representations of the ideas of Pascal center around the character of Bojack. Still, the supporting characters Diane, Mr. Peanutbutter, Todd, and Princess Carolyn further the ideas of Pascal in the show. Diane Nguyen (Allison Brie) plays a human Vietnamese-American writer who meets Bojack in Season 1 because she works as the ghostwriter for his memoir. She is a close friend of Bojack and is married, then later divorces another prominent character, Mr. Peanutbutter. Diane is an extremely pessimistic character, and as the show progresses, we learn that her often ungrateful attitude stems from the fact that she struggles with being happy. “There’s no deep down, I believe that all we are is what we do,” she says in the season 6 finale. She is very different from Bojack because instead of turning to distraction to deal with her internal battles, she is hyper-aware of them, making her very negative. Pascal addresses the human instinct to be a pessimist as he says, “We are generally more effectually persuaded by reasons we have ourselves discovered than by those which have occurred to others”(11). Diane is aware that she is the root of her problems and belittles and bullies herself because she believes in Satre’s theory of radical freedom, unlike Bojack. While Bojack believes life has no meaning, he doesn’t need to be a good person, but Diane constantly thinks about the weight of her actions. The show effectively shows this parallel in the witty and self-aware dialogue. “I didn’t do anything wrong because I can’t do anything wrong. EVERYTHING IS MEANINGLESS! NOTHING I DO HAS A CONSEQUENCE!” says an aimless and sarcastic Bojack. Diane is the contrary as she constantly says things like, “It’s never too late to be the person you want to be. You need to choose the life you want.”

Diane serves as an antithesis to Bojack in terms of the way she faces her problems, but her husband and then ex, Mr. Peanutbutter (Paul F. Tompkins), works as a dynamic foil to the character of Bojack. Mr. Peanutbutter is a half-labrador retriever, half-human character, and like Bojack, he is also a middle-aged former sitcom star. Mr. Peanutbutter is extremely different from Bojack, like Diane, but in an entirely different way. His character is used to highlight aspects of Bojack’s personality; the show constantly compares their personalities. He is happy-go-lucky by nature, and unlike Bojack, he does not take out his feelings of inadequacy or depression on others. While Bojack tears others down, Mr. Peanutbutter lifts them up. Like Diane, Mr. Peanutbutter confronts dilemmas head-on, whereas Bojack runs away from his problems. Mr. Peanutbutter needs constant approval and is addicted to unconditional love, unlike Bojack, who thrives off of self-pity and substances. Both characters struggle with self-hate, but Bojack’s self-hate manifests into self-destruction; Mr. Peanutbutter’s self-hate turns into him doing anything to service his own happiness and comfort no matter how much it hurts those around him. He, too, struggles with understanding his place in the world but handles it in a more composed way than Bojack. “The universe is a cruel, uncaring void. The key to being happy isn’t to search for meaning, it’s to just keep yourself busy with unimportant nonsense, and eventually, you will be dead,” states Mr. Peanutbutter cheerfully to Diane in Season 1, Episode 12, capturing the sentiments harbored by so many when left to ponder what our existence means. This is also evident in Season 5, when Mr. Peanutbutter starts dating a younger dog named Pickles. He cheats on her, and instead of facing the uncomfortable reality of breaking up with her, he proposes to her because he is terrified of being alone after divorcing Diane earlier in the season. Mr. Peanutbutter uses love and affection as a distraction. Mr. Peanutbutter couldn’t be more different from Bojack. Still, he struggles with the same existential problems that Bojack does that are laid out by Pascal, showing how Pensees applies to all types of characters.

Todd Chavez (Aaron Paul) is another one of the main characters of the show. He is a human who lives rent-free with Bojack in his Hollywoo mansion, but throughout the show, he lives with multiple different characters. Todd is lazy and a slacker, and doesn’t have any real direction. While Todd lacks direction, he needs small tasks and jobs to give him a sense of purpose; these are his distractions. As long as he has activities, he is content. While the show humorously addresses this in Season 1, Todd spirals into existential despair when he is left alone with his thoughts. “I need something to do. A job or a task or a direction in life. Do I have a purpose?” This relates back to Pascal’s writing about humans spiraling when left alone with their own thoughts and also brings up another quote from Pensees. “Description of man: dependent, desire of independence, need” (Pascal 50). In terms of Todd, this quote precisely translates to Todd when he says things like, “Hooray! A task!” Todd lives for small distractions like cleaning up Bojack’s house or going to the grocery store to fuel the essential human need for a sense of purpose. Todd is a less complicated character than Bojack, Diane, and Mr. Peanutbutter, but still struggles with the purpose of his existence.

Princess Carolyn (Amy Sedaris) is another vital character on the show whose evolution as a being and character arc display Pascal’s theories on human nature. Princess Carolyn is a pink Persian cat who begins the show as Bojack’s on and off again girlfriend and his agent. Her character is the only character to show substantial growth from Seasons 1-6, and her journey shows that it’s not impossible to have a happy life and not quite understand your life’s true meaning. At the show’s beginning, Princess Carolyn is depicted as a workaholic who struggles to separate her personal and work life; hence, she dates Bojack, her client. She struggles with feeling incomplete as a cat and doesn’t understand why. She tries to use work as a distraction, thinking that her life would be better if she were better at her job. “You gotta get your shit together. So yesterday you let yourself fall in love a little bit, and you got your heart broken. Serves you right for having feelings! Starting now, you are a hard, heartless career gal. Go to work, be awesome at it, and don't waste time on foolish flights of fancy.” Princess Carolyn tries out different lines of work, and as she does this, she begins to discover herself and what she really wants in life, which is to be a mother. She goes through very low points, and in the final season, she ends up with a child and a healthy balance between her personal and work life. Unlike Bojack, she learns from her own mistakes and doesn’t dwell on her past mistakes. She keeps going forward. Out of all the representations of Pascal on the show, she is the only character who proves that it’s possible to use the unknowing nature of life to forge your own path. To quote Pascal, “man wants to be happy, and only wants to be happy, and cannot cease to wish for happiness”(65). Princess Carolyn commits to finding her source of happiness, making her a standout from the rest of the characters. Instead of simply wishing for her distractions to save her, she uses them to discover what she wants.

Bojack Horseman is a postmodernist show that depicts the existential questions that Blaise Pascal writes about in his 1670 book, Pensees, through five relatable and distinct main characters. The characters are all very different, but their overlapping character arcs highlight how they approach the theories Pascal preaches. The show doesn’t take a stance on which character is morally correct in their approach to life, the show encourages the concept of the absurd, an idea explored by philosopher Albert Camus, author of the essay, Le Mythe de Sisyphe (1942). In an essay written by Panumas King titled, Albert Camus and the problem of absurdity,

“Camus defined the absurd as the futility of a search for meaning in an incomprehensible universe, devoid of God, or meaning. Absurdism arises out of the tension between our desire for order, meaning, and happiness and, on the other hand, the indifferent natural universe’s refusal to provide that.”

Camus writes in his essay that “The only way to deal with an unfree world is to become so absolutely free that your very existence is an act of rebellion.” For Camus, the world is irrational and meaningless, but humans are desperate to find reason and meaning in it. After you become aware of said absurd, you can either return to the cycle of daily life whilst being aware of the absurd, refuse to think about the absurd, or commit suicide out of confusion about the absurd. The show shows characters who choose all three choices. Bojack Horseman is aware that existence is potentially meaningless, and after watching six seasons, I believe that the true message of the show is to embrace the absurd.

I don’t know what happens when we die, I don’t know my life’s purpose, but I do know that there are many people and things in my life that bring me happiness, and this show reminds me to hold onto those things because happiness is what we’re all chasing in this life. The absurd is scary and strange, but I find comfort in knowing that every human is on this journey of life together. Life is mysterious and beautiful and every being on this planet is going to interpret its mysteries in their own way. Bojack Horseman is an incredible look at how humans face the same problems. This show changed how I look at the world, I believe that embracing the absurd will save us, at least I believe it saved me from some minor existential crises. How could I not learn so much about the meaning of life from this show? It’s a show about humans and humanoid animals living in peace together.

Works Cited:

Safaoui, Karina. “Can We Reconcile Our Own Mental Health through Animated Shows?” Medium, Medium, 14 Dec. 2021, https://medium.com/@karinasafaoui3/can-we-reconcile-our-own-mental-health-through-animated-shows-484ac071d1d1.

“Pensées.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 12 Mar. 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pens%C3%A9es.

byGarrettCash, Posted. “BoJack Horseman, Pascal, and the Threat of Non-Being.” Love and Mercy, 22 July 2015, https://gcash96.wordpress.com/2015/07/22/bojack-horseman-pascal-and-the-threat-of-non-being/.

Pascal, Blaise, and H. F. Stewart. Pensées. Modern Library, 1967.

K, Megan. “The Postmodernism (and Nihilism) of BoJack Horseman.” Medium, Medium, 16 Feb. 2020, https://kirkwoodmegan1.medium.com/the-postmodernism-and-nihilism-of-bojack-horseman-65dc19083bd9.

The Philosophy of BOJACK Horseman – Wisecrack ... - Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rORIDYHOFTQ.

Bojack Horseman: Addressing Identity | Video Essay | - Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mlfczWYrrFQ.

How to Find Happiness - Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Y02ITNs9eo.

Bojack Horseman: An Accurate Depiction of Mental ... - Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ubbhg3Zwy6g.

What Bojack Horseman Teaches Us about Character Arcs - Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bxZFLsfqssM.

What Bojack Horseman Teaches Us about Character ... - Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2LZd146-xTE.

Bojack Horseman: Writing Relatable Characters - Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ku8GWvE-vhg.

Philosophy - Blaise Pascal - YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3nb4nYqNXyM.

Dunster, Ruth. “Mindfulness of Separation : An Autistic A-Theological Hermeneutic.” Academia.edu, 1 Jan. 2017, https://www.academia.edu/77168100/Mindfulness_of_separation_an_autistic_a_theological_hermeneutic.

Panumas King is a marketing executive for philosophy at Oxford University Press. “Albert Camus and the Problem of Absurdity.” OUPblog, 18 June 2020, https://blog.oup.com/2019/05/albert-camus-problem-absurdity/.