Why Have We Fetishized the Tortured Artist? My Thoughts Post Sam Levinson's "The Idol."

They’re beautiful, practically ethereal creatures with sunken, tired eyes and weak bones. Boxy white shirts with holes and beige stains from last night’s Thai takeout. Matted hair hidden by a team’s baseball cap, whose home city is nothing but a mystery they don’t care to solve. Their inexplicable creations are conceived in messy spaces, half full of nothing of value to anyone on this earth, and the other a treasure chest of remnants of their conscious mind. Their bodies move through this earth like a busy bee in its hive. They are the free-spirited yet tortured artists, few and far between, but with a presence so paramount, how could the rest of the dull social order not fantasize and fetishize this scrivener of alien lands? It’s sexy. They are sexy. They are the ones to cut off their own ear, stab themselves in the chest, overdose, or put a gun in their mouth when confronted with their torment. And we love them. We idolize them. They sit on an eternal pedestal.

Artist fetishization has long been a fixture of mainstream popular culture. In different ways, our society has reduced and simplified the portrayal of an artist, distilling their image into easily replicable and essentialized characteristics—sad, broke, depressed, manic, and incredibly savant. While every profession undergoes some degree of stereotyping, none is as deeply ingrained in the collective consciousness as the enduring typification of the tortured artist. From Van Gogh to Janis Joplin to Elliott Smith, why are we so obsessed with the plagued?

I guess you could say they make for a good story. In our media-saturated world filled to the brim with narratives that are mind-numbingly tedious and exceptionally unengaging, there’s something about peering into the world of a sorry person who communicates their internal struggles with our world through artistic brilliance that is seizing. The legend of the tortured artist is the hero’s journey flipped on its head.

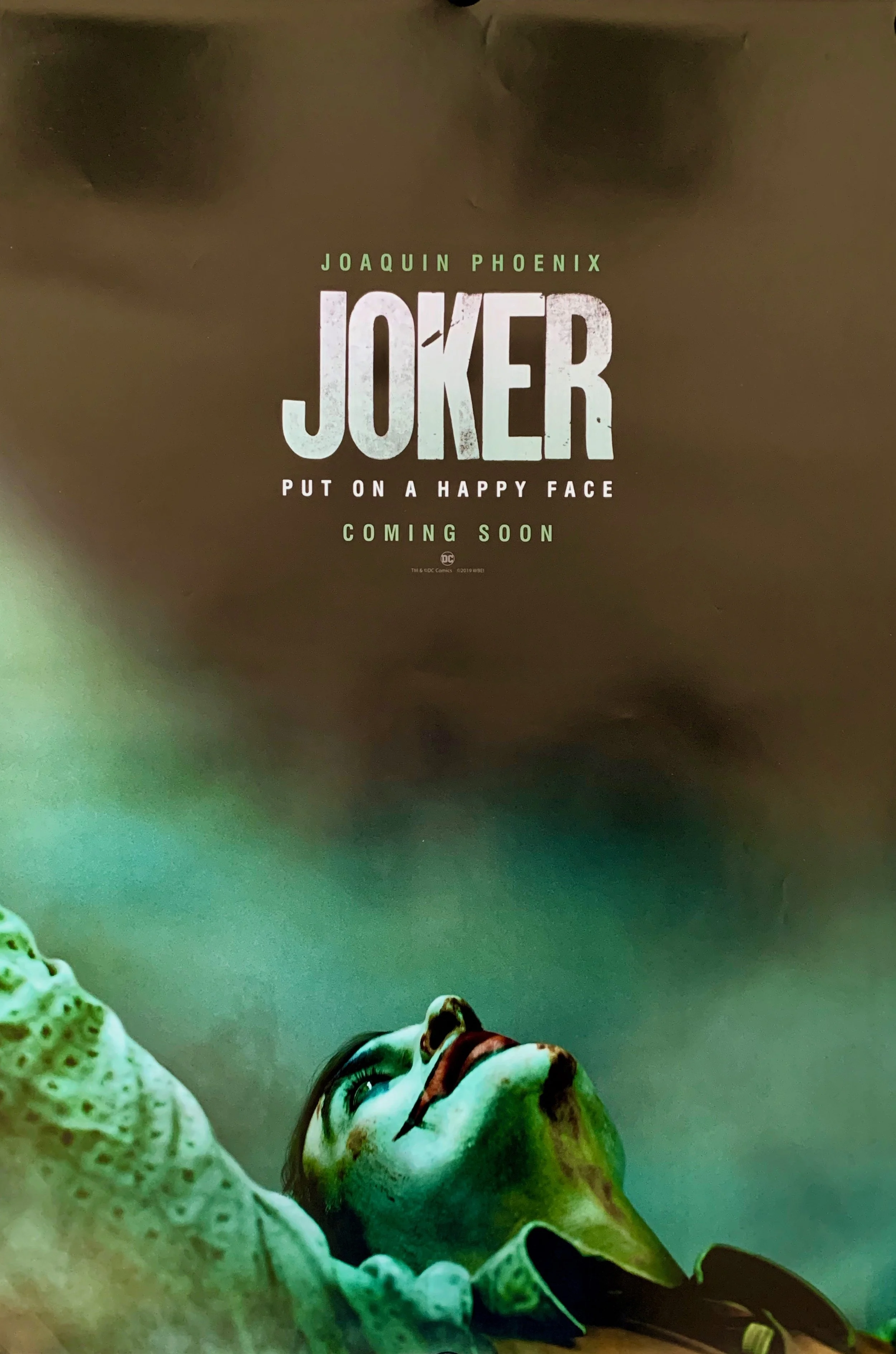

It can be elusive in memory that this truthful trope dates back to the Romantic period when the concept of the passionate genius emerged. Artists like Edgar Allen Poe and, as mentioned previously, Vincent Van Gogh, who grappled with their mental health, became emblematic of this romanticized notion. Their image as suffering artists behind fantastic works like “The Tell-Tale Heart” and “The Potato Eaters” marked them off as people with immense authenticity and heightened creativity. In the present era, we see this same character represented in dramatic films like Black Swan, Whiplash, Birdman, and Phantom Thread. Creating art about a fictitious harrowed artist feels immorally meta, does it not?

The tortured artist embodies this cultural fascination with pain and suffering, as their struggles are perceived to fuel their artistic output. There is often a belief that great art can only emerge from deep emotional turmoil or personal hardships. Suffering isn’t a requisite for innovation, so why does a pioneer like Kurt Cobain’s legacy live half in his tragedy? He was a person before he was a melancholic icon. Does the tragic end of his life transform him from a great artist to a pure mastermind? When we look at figures like Cobain only through their tragedy, they just become a tragedy. When we label them “brilliant but miserable artists,” they become only that. The “tortured artist” label has given us the agency to forget everything meaningful that they leave in their legacy.

Does combining the intrinsic incentive to pursue the fetishized with the extrinsic motivation to pursue the despondent artist fulfill our perverted societal expectations of who is great? While most humans are stuck in a “follow the herd mentality,” artists and the art world are absolutely experts at subverting social norms. Magic isn’t real, but creativity might be the closest thing we have to it. Creativity is a force, a transformative force offering a plethora of possibilities that enable individuals to liberate themselves from the confines of conventional paths. This can account for why countless individuals succumb to the captivating allure of the romanticized notion of the tormented artist.

Sure, it’s romanticizing mental health issues, but the association between cognitive well-being and artistic excellence has long been revered in the cultural zeitgeist. Most recently, in Sam Levinson’s controversial HBO show, The Idol, Jane Adams’s characters rant about the sex appeal behind mental illness. “You people are so out of touch—you college-educated internet people… mental illness is sexy. “If you live in Sioux City, Iowa, you’re never going to meet a girl like Jocelyn. She’s not walking down the street, she didn’t go to your high school, she doesn’t work at the bar or the diner, and she did not marry your best friend. And if—on the off chance—she did, she is still never, ever going to fuck you. Unless she has some very, very serious mental problems.”

The tortured creative is, in fact, even more insidious than our idealized notions would suggest. It becomes distressingly simple to take advantage of artists and their creations when they are already immersed in sorrow, financially, emotionally, and through complicated power dynamics of producer and consumer. The allure of compensating them with mere exposure thrives on the belief that validation is a more precious currency to offer. These elusive figures in society serve as a conduit through which society constructs a hostile work environment that is ripe for exploitation and manipulation and perpetuates misery. Furthermore, they become the vessel through which we rationalize societal inequalities. While we all derive pleasure from the creations of these artists, we tragically fall short of providing them with fair compensation for their labor. Wouldn’t it be the morally correct thing to do to reject this harmful pigeonhole?

I guess.